Six galaxies were trapped in orbit around a supermassive black hole during the early history of the universe, new observations reveal.

The new data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile and other observatories gives astronomers a sense of black hole evolution when the universe was less than a billion years old, according to an ESO statement.

One mystery of supermassive black holes is how they got so large, some containing billions of times the mass of the sun. Supermassive black holes are also relatively common; they lurk at the hearts of most, if not all, galaxies, including our own Milky Way. The new observations give fuel to the idea that such black holes grow in gassy environments within “large, web-like structures,” according to ESO.

“This research was mainly driven by the desire to understand some of the most challenging astronomical objects — supermassive black holes in the early universe,” lead author Marco Mignoli, an astronomer at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Bologna, Italy, said in the statement. “These are extreme systems, and to date we have had no good explanation for their existence.”

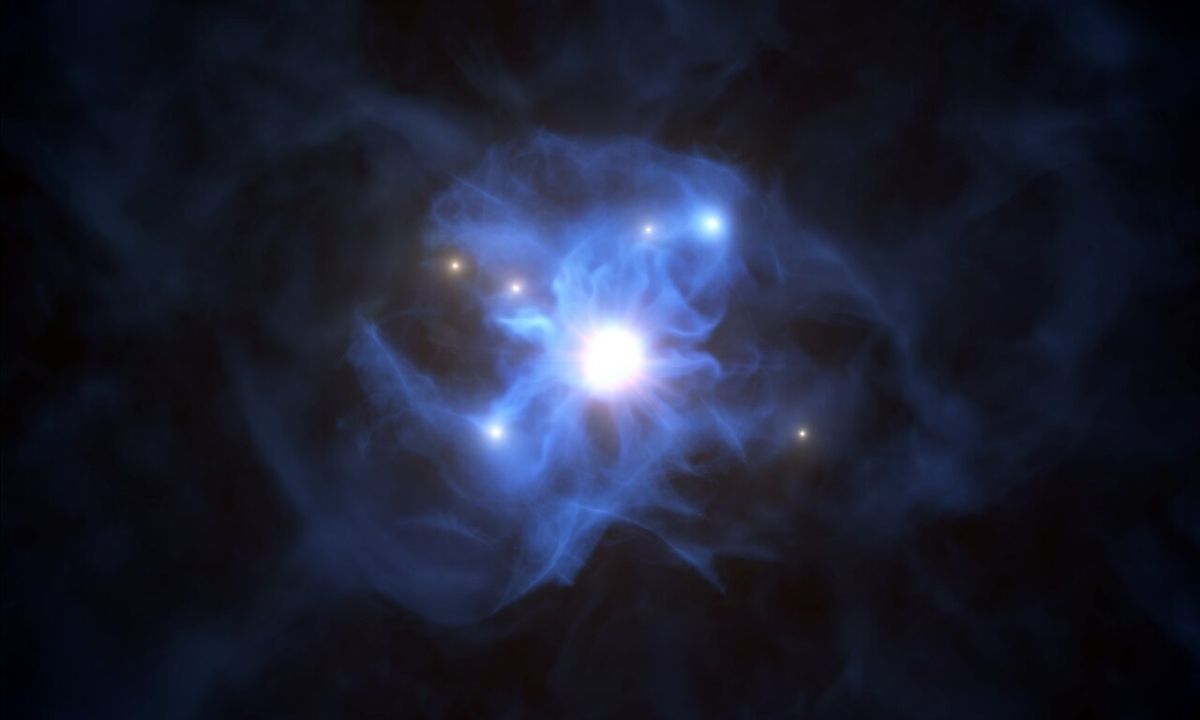

Mignoli said the half-dozen galaxies were found in a “spider’s web” of gas that stretches away from the black hole to a distance of 300 times the size of the Milky Way. The rich gas environment could explain why these black holes grew so quickly in the short time after the Big Bang.

The spider-web structures may have grown out of collections of dark matter, which is a poorly understood substance that makes up most of the matter in our universe, but can only be detected through its gravitational effects. The galaxies in the new research were only a bit easier to pick up: the astronomers required several hours of observations from several large optical telescopes, including the VLT, to study them.

“Our finding lends support to the idea that the most distant and massive black holes form and grow within massive dark-matter halos in large-scale structures, and that the absence of earlier detections of such structures was likely due to observational limitations,” Colin Norman, a co-author on the new research and an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said in the same statement.

Scientists will be able to better study such structures when ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope comes online, as the instrument is designed to peer into the early universe and to detect even fainter galaxies. The telescope’s “first light,” when it will collect test images from the sky, should be in the mid-2020s.

A study based on the research was published Oct. 1 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Source: Space.com